TAKING STOCK

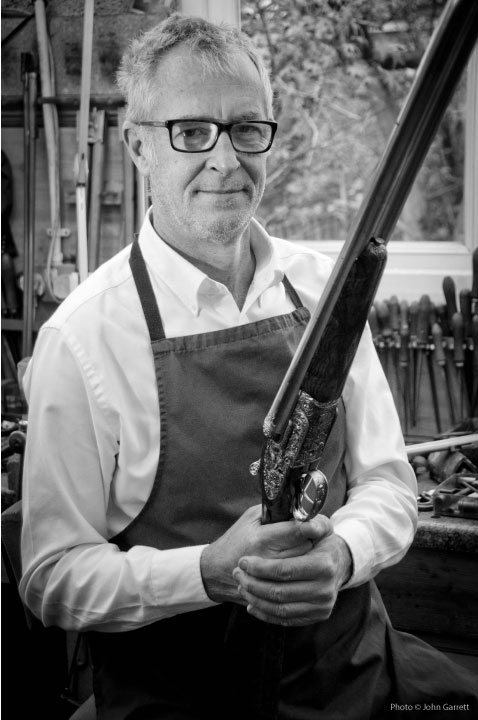

What inspired a local lad to become a fine craftsman? Michael Smith, shares tales of his unlikely journey

Q. Michael Smith, you’re a gunmaker. Where are you from originally?

Shepherd’s Bush.

Q. How has the area changed since you were a kid?

Dramatically. In my road it was predominantly black and Irish working class. We were first generation ‘English’. My parents were Irish immigrants. A lot of the West Indian boys were born here, their parents had come off the boat, like my parents, in the early 50s. We basically lived on the street, played in the bombsite opposite. The front doors were left open all day. No one went hungry – there was always one mother cooking something, whether it was West Indian food, a stew, whether it was this, or that. It was very safe. It was just lovely. It was a community.

Q. What was housing like when you were a kid?

My father met my mother, moved into a three storey house in Shepherd’s Bush. We rented from landlords. Some would call it a slum then. If people saw it now, they’d be horrified.

It would be condemned. We had two rooms and a kitchen, no bathroom, one toilet upstairs shared by three families. There were three boys in our family. The family upstairs had two daughters and a son. I didn’t know any different. My parents own the house now. It worked out for them in the end.

’We were in an era when your “gaffer” was God’

Q. Who lived on the third floor?

On the top floor was an old lady I only knew as Nanny. She was the most unusual woman I’d met. You’d walk into her room: Buddha’s, paintings, violins… objects I’d never seen, objects from around the world. It was like going into ‘Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory’. I was about seven. I think she gave me my passion for art and crafts. Thanks Nanny. She sparked my imagination. Nanny would take me around London. I think on the red buses when you could get that pass for the day. We’d go to galleries, museums. I’d never done anything like that, just created this whole… wow! So I think, anything I’ve got, interest in arts and crafts, or the unusual, started with Nanny.

Q. How do you get into making guns?

A TV programme with Jack Hargreaves called ‘Out of Town’. Sunday afternoons at 12 o’clock. Never missed one. The programme was about thatching, saddle making, coach painters and fly rod makers. This programme just blew my mind really. I didn’t know these crafts existed. At the age of 16 I went to my career teacher, I said: ‘I’d like to be a thatcher, a saddlemaker, or a gunmaker’. The look on his face (considering we’re in the middle of Ladbroke Grove) was surprise. My mother was a cleaner for a family in Notting Hill Gate, she mentioned to them the fact I loved guns and had this idea of been a gunmaker. Luckily for me, the family knew the owner of Purdeys the gunsmiths at the time. I got an interview. Got the job. Started then. My apprenticeship as a gunmaker started at the age of 16.

Alf Harvey (far left) with Purdeys gunmakers

Q. How did your school friends take the news you were training as a gunsmith?

It was quite an unusual thing to say. Most of my school friends became plumbers, bricklayers, electricians. I never wanted to do one of those sorts of trades. I like these unusual mystical trades really.

Q. Who taught you and was he a good teacher?

A lovely guy called Alf Harvey. He was a master craftsman himself, nearly 60 when he took me on as an apprentice. I remember asking him once how he enjoyed his holidays. His reply was: ‘That’s for me to know boy’. That was our only conversation on a personal level that we ever had over five years. I knew nothing about the man. Where he lived, what he did outside of work.

Q. How did that feel as a young man?

Other people would say it was strange but we were in an era where your ‘gaffer’, the man that was going to teach you your trade, was God. You respected them. You wouldn’t talk back. You wouldn’t look away when they were showing you something because if you did, they’d give you a tap on the back of the elbow with a hammer. Old school craftsmen that were passing on their knowledge of 40 years, and if you weren’t willing to listen, you were out the door. My gaffer Alf used to get in at eight o’clock. Same routine every day. Walk in wearing a suit. Go to his bench. Take his bit of cardboard, put it on the floor to stand on. Open up his deck-chair. Take his suit off and change into a different suit. At the end of the day his shirt was still white. His bench was immaculate. Whereas my bench was untidy. My hands would be oily. You would look at these old craftsmen and wonder how they could keep themselves so clean. Magical people.

When one of them died, Georgie Wood. It was a big funeral. Georgie was an East End boy. At the wake after the funeral, everyone was there from Purdeys talking to some of the locals. And someone said: ‘How’d you know Georgie?’ And they said, ‘Well, we work with him’, and they said: ‘So you also work in Tesco’s packing shelves?’ And the guy from Purdeys said: ‘What? No. He works with us. Georgie has been making barrels for Purdeys for 55 years!’. So Georgie had told everybody he knew in the East End throughout his whole life he packed shelves for a living. He never told them he was a gunmaker. Amazing.

’Sir, you are neither a gentleman nor a sportsman, please leave my premises’

Q. Where else have you worked?

I worked at John Wilkes gunmakers for two years. It was on Beak Street, Soho. Soho then was different. All the little houses had tailors, silversmiths – full of artisans down the alleyways, as well as the other side of Soho (sex industry). Mad craftsmen in small rooms making anything from jewellery to tailoring, like Savile Row, to guns, to diamond setters… everything you wanted.

Q. What was it like working at John Wilkes?

I think one of the most memorable things that happened was in the late 70s and an American guy came into John Wilkes. They asked him where he was going shooting and what he was going to do. This American chap said he was going off to Africa to shoot the ‘Big Five’ as it’s called. This used to take years. He was going to blast the ‘Big Five’ in six weeks, not just shoot one, but shoot two or three of each. I remember John Wilkes just looking at him and saying: ‘Sir, you are neither a gentleman nor a sportsman, please leave my premises’. I think it went through one ear then the other. John had to say it again. John was a big guy, not someone to argue with, he’d been a heavyweight boxer in the army, been through the war. He said it again to the client. I think a little bit of the East End came out of him: ‘you can go the right way or the wrong way’. I’ll always remember that quote, ‘You are neither a gentleman nor a sportsman, please leave my premises’.

Q. What type of guns do you make?

Mainly fine English guns.

Q. How long does it take to make a gun?

Building a fine English gun takes between a year and a half to two years, sometimes up to five years depending upon the engraving, who is engraving it, is it having gold inlay, and so on. That’s a long time looking at one gun. You know that gun like the back of your hand.

’Building a fine English gun can take up to five years’

Q. How do you find out what a client wants?

We ask questions, lots of questions. Some clients have gone through the briefing process before so it comes easily. If a Smith & Torok is a client’s first gun we ask even more questions. A gun can take years to build so it is important we do not rush the brief. A brief can take a few hours or sometimes days. They have to be satisfied. We ask what type of gun the client wants, the style of engraving, the wood and the finish.

Q. Why do people ask Smith & Torok for a gun?

I think the reason clients come to us to make their guns is for a personal journey, to work very closely with a small company, to feel that the gun is truly theirs, rather than a mass-produced off the conveyor belt gun.

Q. How does it feel when you hand a gun over to a client?

Before you meet the client with their gun you become anxious. You’ve lived with the gun for years. Something you’ve created. Will the client like it? Will he like the finish? The engraving. Does it balance well? Handover time. You see the client’s face. You see the smile. The joy. And you feel great, absolutely great. Your work has been worth it. You feel great. You feel happy.

Find out more: smithandtorok.com

Editor: Tim Dunn Profile photo: John Garrett http://john-garrett.co.uk

© 2015 Copyright Protected. All Rights Reserved. If you wish to re-use this interview you must seek permission.